Compute Shaders

A shader is a very lightweight program that runs on the GPU, it is designed to be spawned quickly from CPU commands such as dozens or hundreds of different shaders runs every frame. Shader are designed to work exclusively with the resources of GPU, so in term of feature set it’s a lot more restricted than CPU programs (for example you cannot allocate memory on the GPU, you cannot access files on the disk, etc.).

Different types of shaders

The GPU supports multiple kind of shaders, each of them have access to different hardware features and are integrated the different pipelines. In this chapter, we’re interested in the compute pipeline, it is the simplest of all pipelines because it has only a single step.

Compute Pipeline

The compute pipeline on the GPU only allows one type of shader to be executed: the compute shader.This is the simplest type of shader, it’s multi-purpose and doesn’t have access to any fixed hardware function, it’s very good to do general purpose computation on the GPU (GPGPU). Compute shaders are dispatched directly using a number of threads, it is the equivalent of having a job system handling all the boilerplate of starting jobs and distributing work between the workers.

Languages

There are several languages that you can use to write GPU programs, the most popular are GLSL and HLSL. Both languages have very good support for a lot of features and extensive tooling for cross-platform compilation, though HLSL has the upper hand regarding new language specifications as it continues to evolve quickly driven by Microsoft for DirectX advances. For this course, we’ll use the HLSL language but it’s possible to use GLSL as we’ll not be using the latest features released in new HLSL versions.

Syntax

The HLSL syntax is very similar to C with the the twist that there are no pointers, you can overload function parameters as well as a few other extra functionality that makes common operations easier on GPU.

This simple example describes a function that clears a 4 channel image to 0. The entry point of the compute shader (main in this case) is called a kernel.

RWTexture2D<float4> _Output;

[numthreads(8, 8, 1)]

void main(uint3 id : SV_DispatchThreadID)

{

_Output[id.xy] = 0; // notice the implicit cas from int to float4

}

RWTexture2D describes a 2D texture in read/write mode, the type of data in the texture needs to be specified as template parameter. Only a restricted set of types are supported in textures and the number of component in the vectors determines the number of channels in the texture. Note that when declaring a texture, the allocated format on the CPU is not constrained to perfectly match the one declared in the shader, for example a 8 bit per channel texture can be bound to a 32 bit per channel texture to a shader without it complaining. This is because fixed hardware exists to get and set the data on the texture that performs type conversion and/or decompression on the fly.

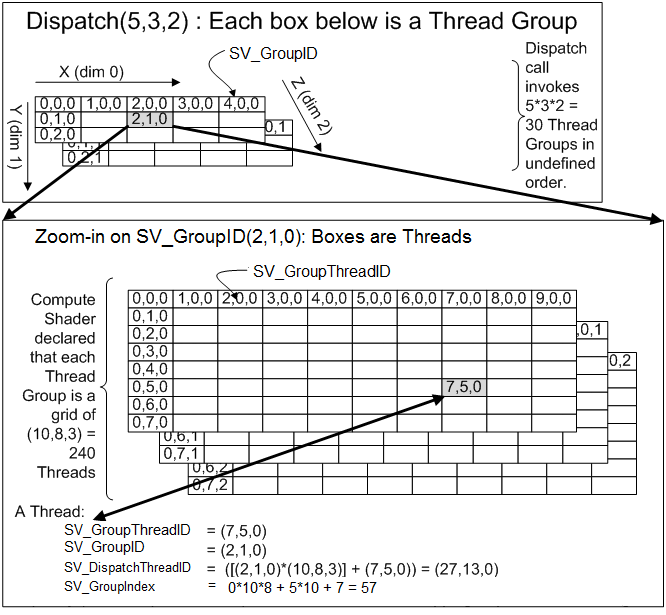

The numthreads attribute on the kernel function specifies the number of threads that can run in a single group, the number of threads is specified by 3 dimension, usually since we’ll mostly process 2D data, we put 8 thread in X, 8 in Y and 1 in Z. When compute shader work is dispatched from the CPU, it’s the number of groups that is specified in the command, which means that the granularity of work on the GPU is actually the group and not a single thread. For this reason, more GPU threads might be executed because it doesn’t exactly match the size of the input data we need to process (in this case we just guard the execution with a size).

Compute shaders are always dispatched by group, a single group share a very fast local memory called LDS (local data storage), this memory allows to share data between the different threads of the group so it’s very useful to write fast algorithms. in HLSL the LDS memory is allocated using the groupshared keyword like so:

groupshared float4 MyArray[64];

[numthreads(8, 8, 1)]

void main(uint3 id : SV_GroupThreadID)

{

uint index = id.x + id.y * 8;

// Initialize LDS data to 0

MyArray[index] = 0;

// ...

}

The kernel have access to all the resources that were bound by the CPU to this compute shader as well as some automatically generated variables. like SV_DispatchThreadID that indicates the “position” of the current kernel in the dispatch, there are several other semantics to know the position of the group or the thread position inside the group:

To know all the special values that are supported in parameter of a compute shader kernel, see the Semantic documentation of DirectX.

To learn more about the syntax of compute shader in HLSL, you can consult the reference documentation: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/direct3dhlsl/dx-graphics-hlsl-reference.

Fullscreen Compute

One very useful application of the Compute Shader is to do a fullscreen pass, this means applying an algorithm to every pixel of a texture. This kind of pass can be used to do post processing effect, apply kernels to an image, apply filtering, etc.

RWTexture2D<float4> _ColorTexture;

[numthreads(8, 8, 1)]

void main(uint3 id : SV_GroupThreadID)

{

float4 color = _ColorTexture[index.xy];

_ColorTexture[index.xy] = color;

}

Note that in a compute shader we can read and write to the same coordinate in the texture, but it’s not recommended to write to different locations because of the many threads running in parallel. If some threads write to the same coordinate, then the result will be random due to the race condition, there is no synchronization happening on the main memory where the texture is stored (this is why it’s fast). So to be able to read from other pixels and write to different places, we just use two buffers: one input and one output